Why did Ulster, now Northern Ireland, become the centre of linen manufacture and trading rather than Dublin? Webb says Sir Robert Kane in 1849: (2)

‘attributed the growth of the linen industry in the north of Ireland not to physical, but to moral causes. In the north the population consisted of a population devoted to industrial pursuits, eager for the independence and power which money confers. In the south the wretched remnants of feudal barbarism paralyzed all tendency to improve. The lord was above industry, the slave below it.’

From its beginnings, Quakers were important in the linen industry in Ulster. As Vann and Eversley say: (3)

‘The Ulster meetings were dominated by the linen trade, since linen-manufacturing families form a far higher proportion of all Friends than do manufacturers of any sort in the south of Ireland. Although their residential patterns would be termed “rural” in the modern sense, the nature of the mill settlements, especially in the Bann Valley, was much nearer a modern urban pattern.’

In the previous chapter, the English Plantation Policy and its roots under Henry VIII were described: small colonies of English immigrants were established in Southern Ireland to pacify and Anglicize Catholic rebels there. Elizabeth I carried on the practice but it accelerated in Ulster after the Nine Years’ War. Prior to that time, that northern province was the most Gaelic of all and the only province outside English control. But most of the Catholic landlords in Ulster abandoned their estates in the 1607 Flight of the Earls and sought Spanish assistance in their fight against the English. In return, all their lands were expropriated and English, Scottish and Welsh proprietors were brought in to take their place. In turn, they brought in many tenants to work their new estates. (4)

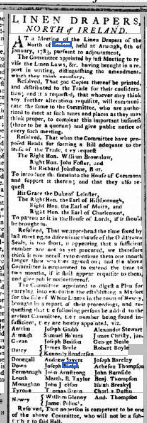

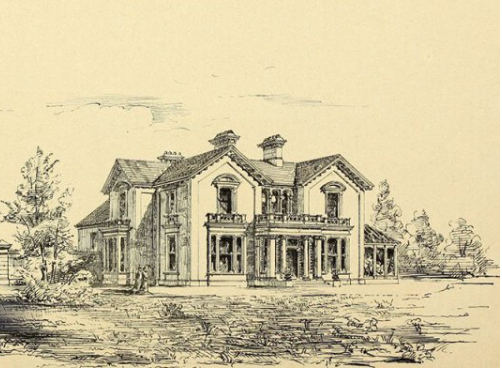

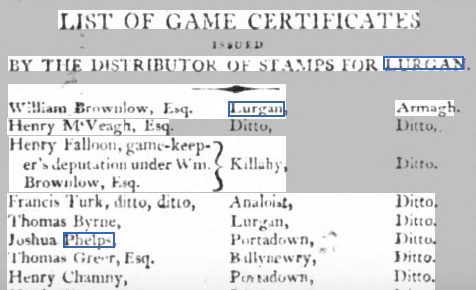

As part of the Plantation Policy, William Brownlow (1591-1660) from Nottingham was knighted in 1622 and granted lands around Lurgan and in 1629 a patent for a weekly market and two annual fairs there. Bit by bit he came to own over 15,000 acres, the second largest private holding in County Armagh. His grandson, Arthur Chamberlain Brownlow (1645-1712), inherited the estate and represented County Armagh in the Irish Parliament from 1689 till his death. He dedicated himself to the development of his lands around Lurgan, welcomed weavers and tanners as his tenants and granted them renewable leases. He organized the weekly markets and both bought and sold their linen products. His successors continued to support that industry for generations. (1) In 1803, one of Arthur’s successors opened a private bank called William Brownlow Esq., & Co. By 1815 the bank was called Malcomson & Co. and its Dublin agents were Wilcocks and John Phelps. (more below) The sumptuous Brownlow home shown below was built in 1836 to replace earlier buildings destroyed by fire or age. The family ran out of funds and moved to London in 1893 and the house was sold to the Orange Order in 1903. (4)

Typically, flax growing, spinning and hand loom weaving stayed on the farms while linen drapers/merchants traded for the brown unbleached linen in the village streets. They settled up in the local inns and took delivery then carried on with bleaching the cloth before selling it on to traders in Dublin or England.

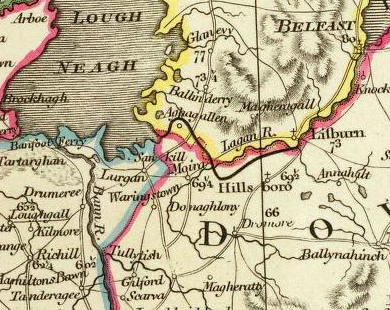

The village of Lurgan, about 20 miles southwest of Belfast, was an ideal location for both the Quakers and the linen industry: it was unwalled, non-corporate and guild-free and became the marketing centre for the entire region. A visitor described Lurgan as ‘at present the greatest mart of linen manufactories in the North, being almost entirely populated with linen weavers and all by the care and cost of Mr. Brownlow’.

William Edmondson moved to Lurgan in 1654 and soon established the first Quaker meeting in Ireland. In his words they: (5)

‘met together to wait upon God and to worship Him in spirit and truth. The Lord’s mercy and goodness were often extended to us to our comfort and confirmation in the appearance of His blessed truth received in our hearts’.

The 1660 Restoration brought the Act of Uniformity and the Conventicles Act. Quaker worship was then illegal and they were increasingly persecuted. Locally, the Lisburn Anglican bishop was intent on protecting the dominant position of the Church of Ireland but in Lurgan the influence of Arthur Brownlow tempered the impact of the law. He continued to welcome Quaker tenants: ‘he always showed the greatest kindness and indulgence to all Protestant Dissenters, which surely ought never to be forgotten by them’. Accordingly, many of the transplanted English and Scots in the town were Quakers. Lurgan’s importance to Quakers in Ireland was demonstrated by George Fox’s visit in 1669 and by William Penn’s preaching there in 1698. By 1693, Lurgan had 14 Quaker families and in 1703 they made up 1/3 of the property holders. By the middle of the 18th century, Lurgan had grown to some 4500 people thanks to linen production on the nearby farms and its weekly linen market. (6)

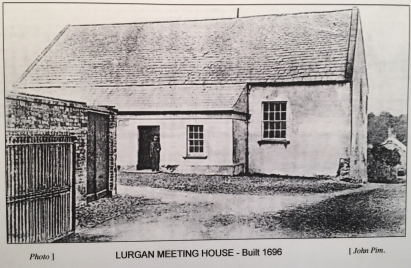

Lurgan Quakers were particularly valued because of their contribution to its economic health and their business links with Quakers in Dublin, England and America. Before 1681, a school master was engaged following George Fox’s advice to have schooling for both boys and girls ‘that they might be instructed in all things civil and useful in creation’. After the Williamite Wars, Lurgan Quakers no longer found it necessary to meet privately and they leased Brownlow land for a meeting house and cemetery. The minute recording this decision said: (7)

‘In the year 1695 it pleased God to open the hearts of the Friends of this meeting to build a meeting house fit for a province meeting or other large meeting – the usual one being too little and going to decay. So Friends upon several conferences ordered affairs so as the said house is built upon a tenement called Maddrin’s tenement of the south end of the town of Lurgan upon copyhold lease from Esq. Brownlow, in the name of Robert Hoope, being for this meeting’s use, and likewise two small dwelling houses in the front of the said tenement, the cost of which with the meeting house by subscription as hereafter mentioned, but what wanted to complete the said work was paid out of the collection stock which was but little’.

The stone building was completed according to Brownlow specifications, paid for by October 1697 and conveyed to leading members for the ‘sole use, service and interest of this meeting’. Quaker meeting houses at that time were remarkably similar with a low ministers’ gallery facing rows of benches for the congregation and a part of the room set aside for separate business meetings. With this new structure, the Lurgan meeting attracted more members and the town became the acknowledged centre of Quakerism in Ulster. This building served the local Quakers almost 200 years.

Linen produced in the Lurgan area was of high quality and so brought high prices. As a result, the surrounding area supported a relatively high population. Now we start to see the emergence of families who became the great and most wealthy Quakers in all Ireland. John Nicholson set up his business and improved bleaching practices on the River Bann near Gilford. James Bradshaw was licensed as a linen inspector and sent to Europe to learn their methods. The Greer family became important merchants in Ulster and later intermarried with the Malcomsons. (8)

Alexander Christy, born 1642, brought his family from Aberdeen, Scotland, in 1675 and acquired the Townland of Moyallen, Parish of Gilford, about five miles south of Lurgan. Experienced in textile making, they developed improved bleaching techniques and attracted Quakers experienced in the linen trade to Moyallen along the River Bann.

The Ulster Quarterly Meeting authorized a branch meeting in Moyallen as follows: (7)

‘At a meeting at Ann Webb’s the 16th of 2nd mo. 1692 some Friends now dwelling at Moyallon near Knockbridge who finding themselves so remote from all meetings have offered their desire of keeping a meeting amongst themselves, which being considered this meeting gives consent that the said Friends may have their request in respect to keeping a meeting, provided they may not thereby be separated from Lurgan Meeting (being formerly of it) but from time to time be subject as required upon occasion.’

After years of meeting in private homes, Alexander’s grandson, John Christy (1711-1780), now prominent and successful in the linen and bleaching business, provided land for the meeting house in 1736. It was enlarged by his fifth and youngest son, Thomas Christy, in 1780 the year of his death and a clear title given ‘for a Meeting House and Graveyard for the said Society of the people called Quakers, for ever, and for no other trust, use, intent or purpose whatsoever’.

Thomas Christy’s son, John, drowned in 1758 and the property passed to the Wakefield family and later to the Richardson family who still own it. Since those beginnings, the Moyallen meeting house has played an important part in Quaker life in Northern Ireland and is listed as being of ‘Special Architectural and Historic Interest’. The Quaker school was established there in 1788 and since 1934 a summer camp has been held on the property. (7)

J. M. Richardson, a descendant of the families involved, wrote in 1894: (9)

‘In 1685, the townland of Moyallen was granted to a colony of the Society of Friends in England whose descendants still maintain and have contributed greatly to the prosperity of the surrounding district. Here a meeting house since renovated, was built in 1723 and in 1710 a member of the Christy family seems to have introduced the bleaching of linen, a new industry in that part of the country’.

With Christy leadership, linen making boomed around Moyallen. By 1772, there were 26 greens on the River Bann for ‘grassing’ or laying out linen in the fields to bleach.

Returning now to our ancestors, we recall that Thomas and Sarah Wilcocks Phelps came north to Moyallen in the mid-1770’s. He was already well known there and by 1777 was a trustee of the Lurgan meeting. He became a trustee of the Moyallen meeting as well and lived there mainly until his early death 29 August 1787. (10) It is said that he ‘was with others largely instrumental in the introduction of linen manufacturers into N of Ireland’. (11) On 18 March 1788 the Belfast Newsletter reported his death as follows:

Sarah Wilcocks Phelps gave birth to 13 children. The lives of the eight who lived to adulthood are described below. (12)

Hannah Phelps, born 3 August 1743 and died unmarried 19 October 1777.

Mary Phelps, born 28 October 1744, was active in the Dublin meeting all her life with occasional visits to the Lurgan meeting. She was regularly listed among the Dublin nobility and gentry and owned property in County Tipperary. Mary died unmarried at her home on Waterloo Road in Dublin 20 June 1828.

Elizabeth Phelps, born 14 January 1745, known as Pretty Betty and died in Lisburn 5 July 1832. In Dublin on 13 October 1771 she married Jacob Hancock, Jr. (1749-1793), after the romantic courtship indicated in Jacob’s letter below. (13)

‘My Dear Betty,

Where shall I find words suitable to express the feelings of my heart, or Terms adequate to convey the unabated Glow & Warmth of my Affections? Were I turn Plagiary and rob the studied Labours of Antiquity of their most dignified and exalted Sentiments, or were I assisted with all the boasted Expressions of modern Literature, yet after all, when Language has done its utmost, there would be something left behind, there would be a Chasm or a Vacancy still remaining, which can only be supplied by the Conception of Thought or by by the secret Contemplations of an abstracted Silence…’

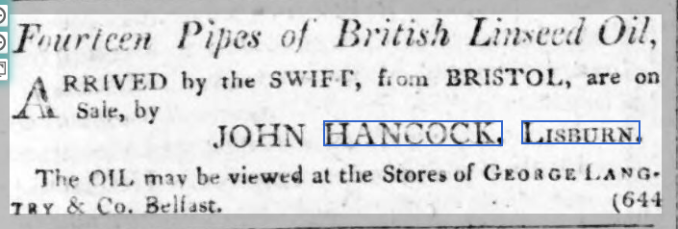

Jacob Hancock inherited several properties as well as a linen production business around Lisburn. He did well in that trade and left Betty a considerable fortune. He and his half brother, John, were approved by the Linnen Board as linen lappers. John, bequeathed £ 1000 to buy the land for the Friends’ School in Lisburn, founded by Elizabeth Fry in 1774. (more below)

None of Jacob and Elizabeth’s three sons stayed in Ulster. John, the eldest, born 1779, took the family Bible, went to the United States and disappeared. Thomas (1783-1849) married Hannah Wakefield Strangman in 1810 and was successful as a doctor in England. Jacob Bradshaw Hancock (1788-1844) was a scholar who married Mary Hubbard in 1830 and emigrated to Cincinnati, Ohio. The five daughters were Sarah (1772-1847) who in 1796 married Samuel Greer, a prominent linen trader in Lurgan, and had 11 children, Mary (1773-1828) who married James Hogg in 1822, Elizabeth (1777-1832), Isabella (1786-1872) who married William Steele-Nicholson in 1807 and had nine children, and Anna (1791-1820). (7)

Joseph Phelps, born 5 August 1747 – more below.

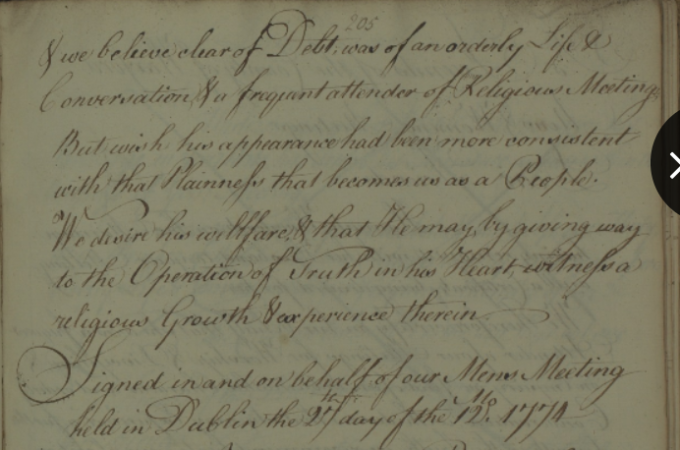

Wilcocks Phelps, born 23 October 1748, married Sarah Denman (1761-1834) of Bristol on 17 August 1782 after receiving the customary clearance from the Dublin meeting. (12)

Sarah remained an active and devoted member of the Dublin meeting until her death, often charged with organizing its poor relief. Three of their sons, John born 1784, Joseph Clarke Phelps (1786-1816) and William born 1789, in time were all disowned by the Dublin meeting. Their daughter, Elizabeth, born in 1788, in 1811 married George Fennell of County Tipperary, an increasingly important family. Wilcocks and Sarah’s three later children were Anna Maria born 1792, Celia (1793-1794) and Charles Wilcocks Phelps born 1794. (12)

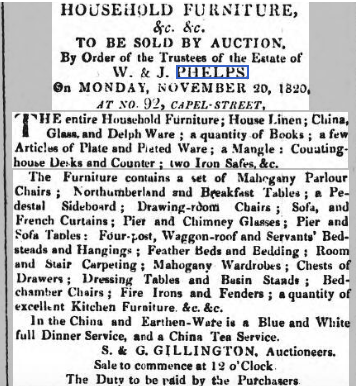

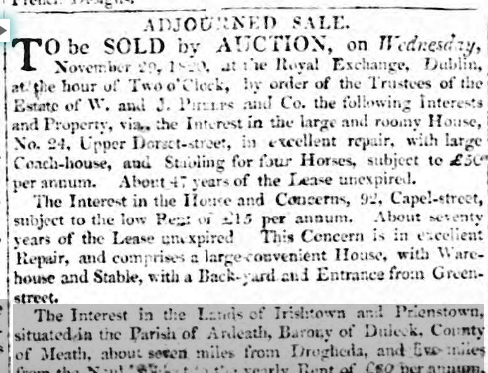

With his brother John, Wilcocks Phelps worked as a banker and merchant trader in Dublin arranging, for example, one shipment of 17,000 pieces of Irish linen for the London market in July 1784. (17) After Wilcocks’ death, 9 May 1818, the firm’s bankruptcy compelled the sale of the family’s handsome furnishings as advertised in Dublin newspapers.

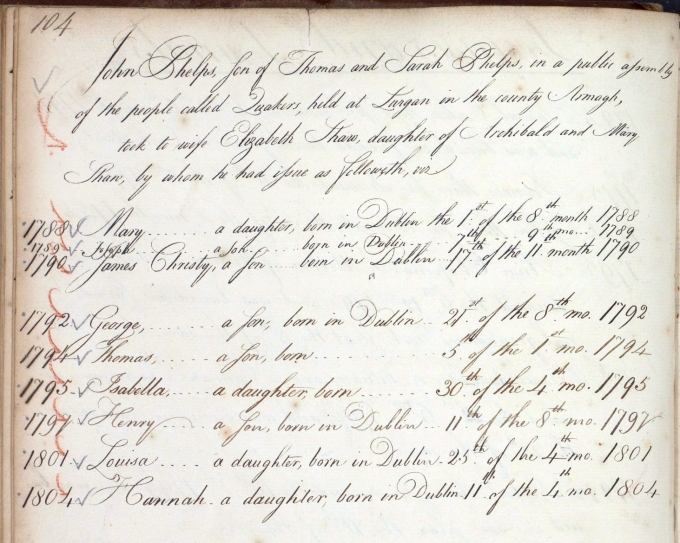

John Phelps was born 23 July 1750 and lived until 20 January 1823. He was listed among important Dublin society in 1783 and married Elizabeth Shaw (1766-1850) in Lurgan 20 December 1786. The Dublin Quaker meeting’s record of their nine children, all born in Dublin, follows.

Four of the children, Mary, Joseph, Henry, and Sarah, remained members of the Dublin meeting for decades contributing along with their mother a regular 10 shillings each half year. The second son, James Christy Phelps, was certified as a journeyman apothecary in 1805 but soon left for Australia. (12) By 1823 he was first secretary and cashier of the Bank of New South Wales and the owner of large land holdings. James Christy married Elizabeth Forster Orpen, ‘a young and amiable widow’ in Sydney in 1828 and was accordingly disowned by the Limerick meeting. In 1837 he served on a jury in a NSW Supreme Court trial and in 1854 was appointed Commissioner of Crown Lands for the Paterson District. He lived and died in 1873 at Gostwyck, N.S.W. on the Paterson River leaving four children: John Shaw Phelps, Marian Phelps Dangar, Elizabeth Phelps Dangar and Mary Phelps.

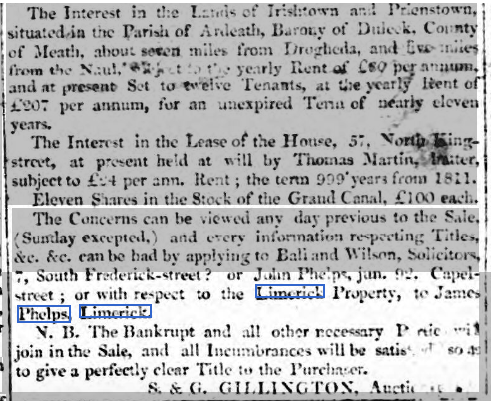

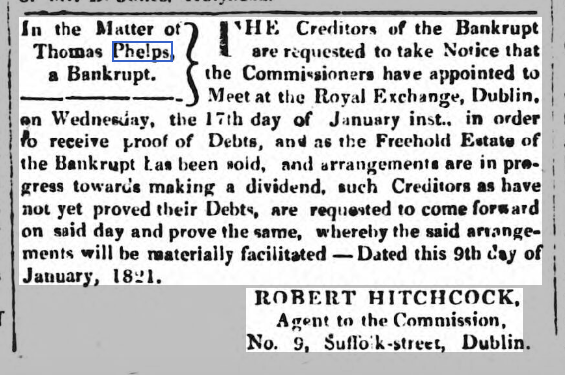

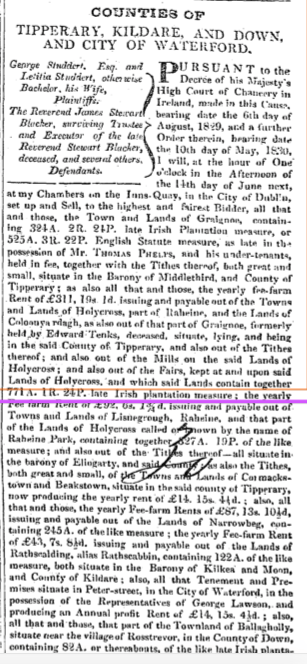

Despite their 1802 bankruptcy, John and Wilcocks Phelps carried on in business together in Dublin. They were the sole agents for the Malcolmson & Co. bank, originally William Brownlow Esq. & Co., and ran the only office where its notes totalling £ 170,000 could be redeemed. The bank lost heavily during the last years of the Napoleonic Wars. Wilcocks’ eldest son, John, succeeded him and the two Johns resorted to business practices which today would be illegal. In 1820 they were obliged to auction off their various properties in Dublin as well as in County Meath along with shares in the Grand Canal. The sale advertisement below was in the Belfast Newsletter.

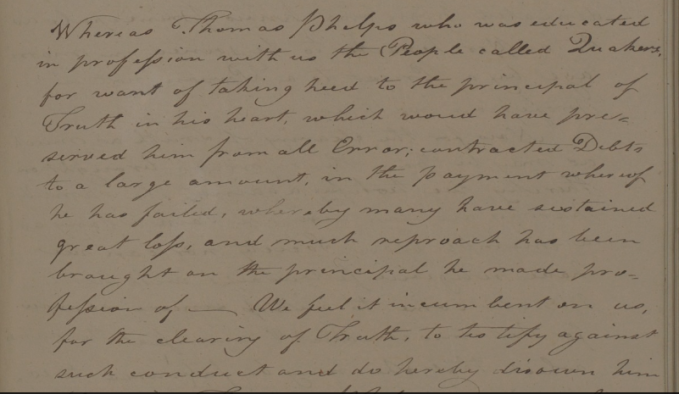

In January 1821, John and Wilcocks were disowned by the Dublin Quakers and John Phelps replied: (12)

‘If the meeting taking a different view of the case from what I have been able to do should judge it necessary to proceed to extremity I will endeavor to submit with resignation. As regards my general conduct as a member I am conscious that I have in too many respects acted inconsistently but I trust I have not been insensible to the value of communion with the religious Society in whose principles I have been educated and I hope that the impressions arising therefrom may remain although the bond which united me should be severed.’

Thomas Phelps, born in Dublin 9 November 1755, was a successful linen trader and acquired various properties in Moyallen from the Christy family. He died unmarried 4 February 1810 after a long illness. The Belfast Magazine in its 1809-1810 issue published a substantial laudatory elegy:

At Moyallon, in the County of Down, Thomas Phelps, Sen. an eminent linen draper. He was a man of the strictest probity joined with an openness and a pleasing freedom of manners which conciliated the esteem of his acquaintances, and in as especial manner the regards of the poorer classes of society, with whom his expensive trade brought him acquainted, particularly in those excellent schools of equality, the markets for the sale of brown linen. His liberalities to the poor were extensive, and his purse was ever open to promote plans of usefulness, to clothe the naked, and instruct the ignorant by the encouragement of schools. “Slave to no sect, he took no private road,” but his religion was of that practical kind, which consisted in doing good, and regulating his heart, and having made these essentials his prime concern, he did not suffer a large arrear to be settled on his death bed, as too many do, who trust to certain ceremonies to be then practiced, and certain anxieties to be then indured to atone for the habitual neglect of duties through life. Consequently the approach of death brought no terrors, and having lived in regular preparation he was free from the fears which often torment in the last moments of a misspent existence; and to which also some well meaning people sometimes give way and make their lives unhappy by an unprofitable fear of death, while others live as if they were never to die. Free from both extremes, he bore a long and painful illness with patience and resignation, and has left a lasting memorial of esteem in the memory off his friends. Without giving way to the fulsome style of panegyric too common in recording deaths, it may be allowed, to give the due meed of praise to departed worth, not to gratify the vanity of surviving relatives, but to hold up a conduct worthy of imitation to all. In recording a brief memorial of such characters, the impressive language is held out. “Go thou and live likewise”

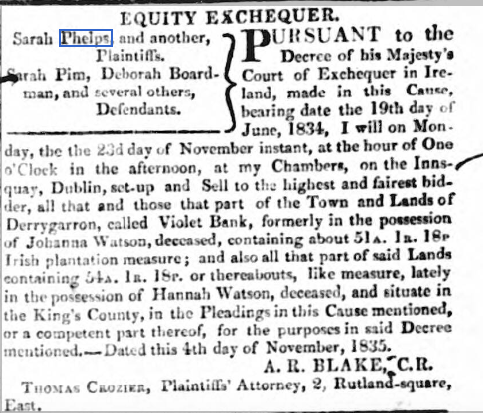

Sarah Phelps was born 8 November 1765 and died unmarried in Moyallen 4 July 1834. (10) Legal notices indicate that she held property and mortgage interests elsewhere in Ireland.

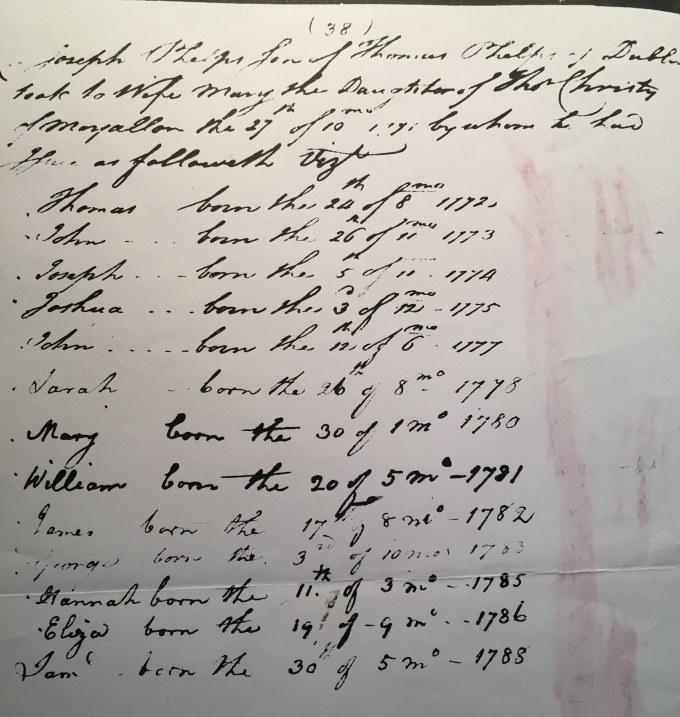

On 27 October 1771, Joseph Phelps married Mary Christy, born in Moyallen 1 September 1750 and the daughter of the Thomas Christy who gave the property and built the meeting house there. She lived until 8 July 1838. Their marriage declaration followed the standard pattern showing the typical Quaker commitment and community involvement: (14)

‘Whereas Joseph Phelps son of Thomas Phelps of the City of Dublin & Mary Christy Daughter of Thomas Christy of Moyallen in the County of Down, having Declared their Intentions of taking each other in Marriage Before Several Meetings of the People called Quakers at Lurgan, According to the good order used amongst them…whose Proceedings therein after a Deliberate Consideration thereof with Regard to the righteous law of God & Example of his People recorded in the Scriptures of truth in that case Where approved by the Said Meetings they Appearing Clear of all others & having the consent of Parents & Relations Concerned, & their said Intentions Being twice Published in The Respective Meeting to which they belong and Nothing appearing to obstruct….. Now these are to Certify all whom it may Concern that for the full Accomplishing of their said Intentions this 27th day of the Tenth Month Called October in the year of our Lord One Thousand Seven Hundred & Seventy one, they the said Joseph Phelps & Mary Christy Appeared in a Public assembly of the Aforesaid People Met together to Worship God at their Public Meeting place in Moyallen Aforesaid, & in a Solemn manner the said Joseph taking the said Mary Christy did openly Declare as follows Viz………. Friends you are Witnessing that I take Mary Christy to be my Wife Promising thro Divine Assistance to be onto her a Loving & Faithful Husband till Death Separate us……Then and therein the said Assembly the said Mary Christy did in like Manner Declare as followeth Viz…….. Friends you are Witnesses that I take Joseph Phelps to be My Husband Promising thro Divine Assistance to be onto him a loving and faithful Wife till Death Separate us…………. The said Joseph Phelps & Mary as a further information thereof did then & there to this ??? & their hands as Husband & Wife And (those) whose Names are hereunto Subscribed being present at Solemnizing of their said Marriage & Subscription in Manner aforesaid as Witness hereunto have to these presents Subscribed our Names the day & year above.’

The signatures of all the 56 people witnessing the ceremony follow.

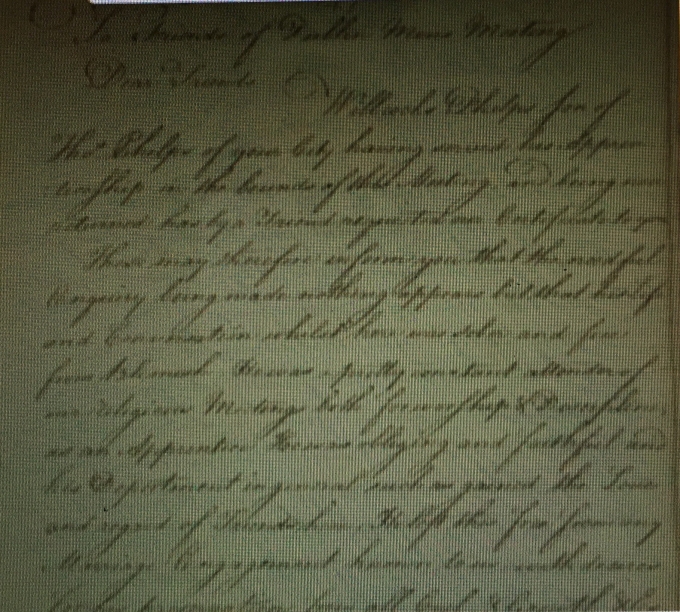

Joseph Phelps was all known and respected in the Lurgan meeting by 1774 when his signature appears on two of its documents. His certificate of removal from the Dublin meeting was received by Lurgan Quakers 5February 1775 and is shown below. (10)

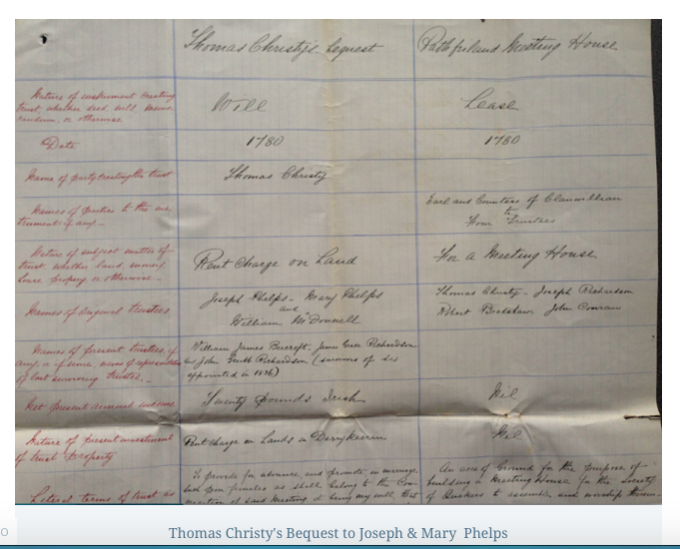

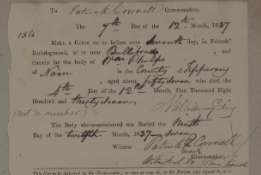

At his death Thomas Christy bequeathed him 500 pounds and several pieces of land. Both Joseph and Mary were trustees of her father’s estate and for the land that he gave for the Quaker meeting house as the document below shows. (14)

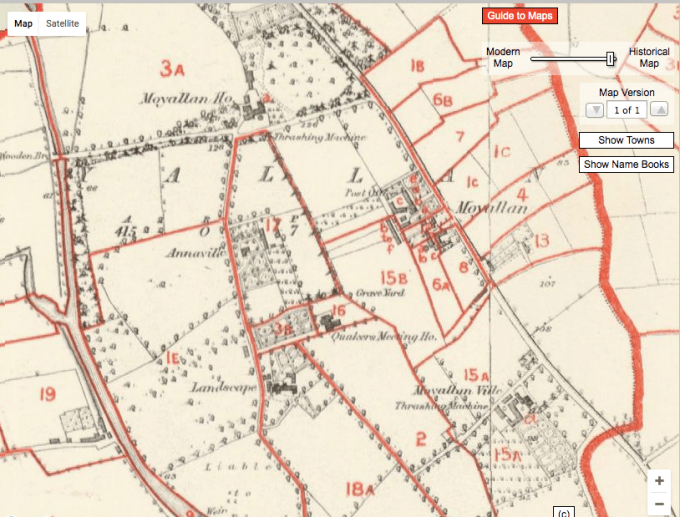

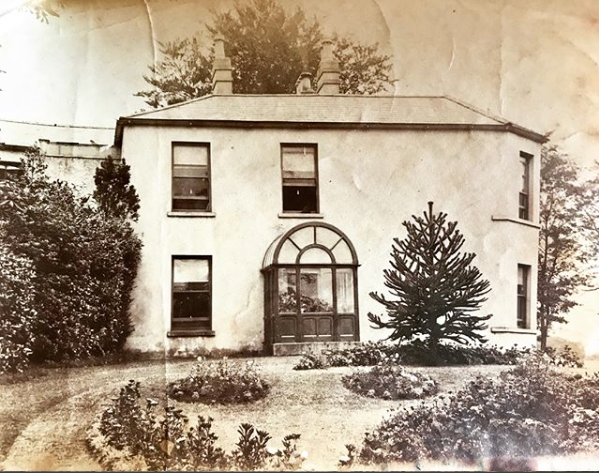

Joseph enjoyed considerable financial success from linen trading and was a member of a ship owning syndicate with the Christys as well. They lived in Moyallen Ville or Manor south of the village shown in the map below. His nephew and niece, George and Elizabeth Phelps, inherited the property and passed it on to their niece, Anna Sophia Phelps, Joshua’s daughter who stayed in Ulster. (7)

North of the village stood Moyallen House, the home of the Christys. This fine home was destroyed by fire in 1845 but rebuilt by the Wakefield-Richardson family. The Christy, Wakefield, Richardson, and Phelps families, all devout Quakers, worked, married and carried out many business transactions together well into the 20th century. (9)

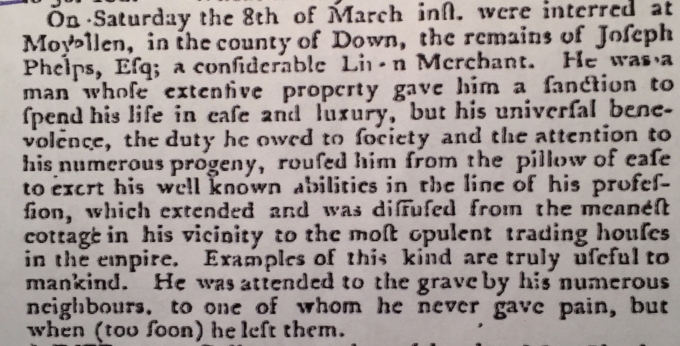

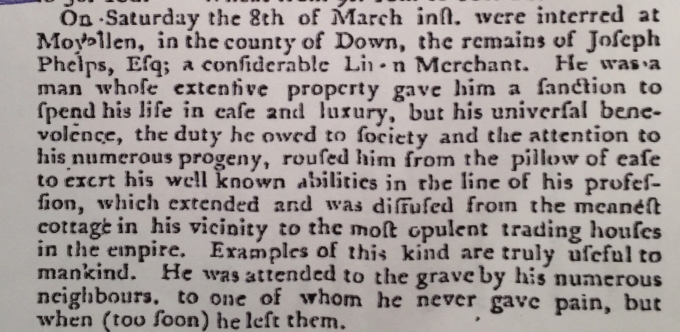

Like his father, Joseph was not a Trustee of the Board of Linen Manufacturers but he was highly regarded in the industry. His early death on 5 March 1787 was reported in the Belfast Newsletter on 18 March 1788 as follows: (22)

The Belfast Newsletter on 9 November 1790 also published an ‘Elegy on the death of Joseph Phelps, Esq. late of Moyallon, in the Co. of Down’. Tedious and 43 verses long, it still makes clear that Joseph was both successful and much admired in the community. This tribute can be found as Appendix 5 in my 2009 booklet, ’The Bell and Phelps Family Histories’.

Linen trading had produced considerable wealth for the interrelated Quaker families and leading Quakers in and around Moyallen had several fine homes such as Moyallen House and Moyallen Ville. However, such opulence and the apparent abandonment of traditional Quaker simplicity did not go unnoticed: an American visitor wrote: (15)

‘Friends in Ireland seem to live princes of the earth more than in any country I have seen. Their gardens, houses, carriages, and various conveniences, with the abundance of their tables, appeared to me to call for much more gratitude and humility than in some instances.’ (??)

The last decade of the 18th century saw all of Ireland shaken by a bloody rebellion. Inspired by the French Revolution, the United Irishmen from 1791 sought to unite Catholics, Protestants and Dissenters such as Quakers in securing republican reform of the Irish Parliament. French participation was planned and only bad weather prevented the landing of 14,000 French soldiers in Southern Ireland in 1796.

Hoping to restore the suppressed Catholic religion, the rebellion in southern Ireland evolved into a movement against Protestant landlords. Northern rebels largely maintained their anti-sectarian views and their demand for local control of their affairs. Everywhere the rebellion brought extreme reaction from the Dublin powers: torture and multiple hangings became the norm. The rebellion finally ended in early September 1798 despite the 1,100 French soldiers still involved. Between 10,000 and 25,000 rebels including many non-combatants lost their lives and much of the countryside was laid waste. (4) Quakers suffered with their neighbours but struggled to stay neutral in the fighting while aiding those of any religion when they could. (5)

In addition to the cost of the rebellion in losing people and agricultural production, economic and social changes in the late 18th and early 19th century affected all of Ireland, the solidarity of the Quaker communities and the Phelps family.

The Lurgan Quaker minute book below shows all Joseph and Mary’s children. (15)(20)

As these twelve lives are described, several of the great Irish Quaker names show up again and again. e.g. Pim, Lecky, Malcomson, Harvey, Robinson, Hancock, Richardson, Wakefield, Richardson, Newsom and Christy. As an example, at one wedding in 1846, Joshua Pim Richardson, son of James Nicholson Richardson, married Susannah Lecky Pim, daughter of Joseph Robinson Pim. Quaker business partnerships and corporations were similarly interlinked. As R. S. Harrison said: (8)

‘The family was the prime unit of business organization. It represented a survival mechanism and the safe maintenance of capital was a central part of its strategies. Their business activity was highly regionalized and localised particularly in investment terms. Much business was base on a central family partnership perhaps with a brother-in-law or cousin’.

The lives of Thomas and Mary Phelps’ children are described below.

Thomas Phelps was born in Dublin in 1772 and, after his father Thomas’ early death, immediately took up responsible roles in the Lurgan Quaker meeting. As treasurer in 1796 and in 1799 he was ‘desired to do the needful’ re school fees and clothing for the needy. He was one of the Lurgan’s representatives to the Ulster Quaker half-yearly meeting through the 1790’s but he and others found their views at odds with traditional Quaker discipline and out of step with the life they were experiencing. Their financial success and contacts with more worldly non-Quaker businessmen plus the appeal of Methodist preachers showed how impractical the Quaker closed society was. Other Quakers had difficulties over parts of the Bible. Visiting American ministers led to confrontation between the ‘New Lights’ and Orthodox Quakers. The following quote shows how Thomas figured in one such disagreement at the 1800 Ulster quarterly meeting: (16)

‘Soon afterwards Thomas Boardman, of Dungannon, Thomas Phelps, of Moyallen, James Christy, of Stramore, John Davis, and Hannah Davis, of Lurgan, who were all in the station of elders, and members of Ulster quarterly meeting, declined the attendance of meetings for discipline, because they could not unite in the measures attempted to be carried into effect in those meetings, nor with the persons who were now become most active in them.’

The next year, an unauthorized marriage attended by many prominent Quakers at the Friends School in Lisburn resulted in Thomas and five others Lurgan members being disowned. Within two years, the Lurgan meeting lost 26 members through disownment or resignation. The Lurgan minutes say: (16)

‘This meeting having resumed the consideration of the conduct of Thomas Phelps, James Christy, William Dawson, Samuel Sinton, Hannah Davis, and Sarah Dawson, who have been under dealing for being present, and aiding at a disorderly union of a member of our society, with a person not in unity with us, and who been in the practice of absenting themselves from the attendance of our religious meetings…we think it right at this time to clear ourselves from the imputation of encouraging such irregular conduct; and declare that we cannot hold unity with them therein, nor consider them as members of our society, until they experience and express condemnation therefor.’

Disowned by the Moyallen meeting, Thomas apparently tried his hand at banking in England. On 9 November 1801, Thomas married Charlotte Charity Lloyd (1776-1803), granddaughter of Sampson Lloyd II of Bordesley, Warwickshire, a prominent Quaker iron maker and in 1765 the co-founder of Taylor’s and Lloyd’s Bank in Birmingham. For 12 years Sampson was elected President of the Association of Chamber of Commerce of the United Kingdom. (Lloyd history)

Charlotte was the tenth of her mother’s 15 children but died a year after the birth of their son, Joseph Lloyd Phelps. He was educated in Ulster but then returned to England and much later in life wrote a strong letter supporting ‘Ireland for The Irish’. In that letter he describing himself as a nephew of George Phelps of Moyallen, ignoring his father Thomas.

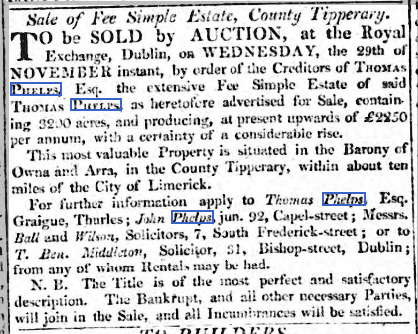

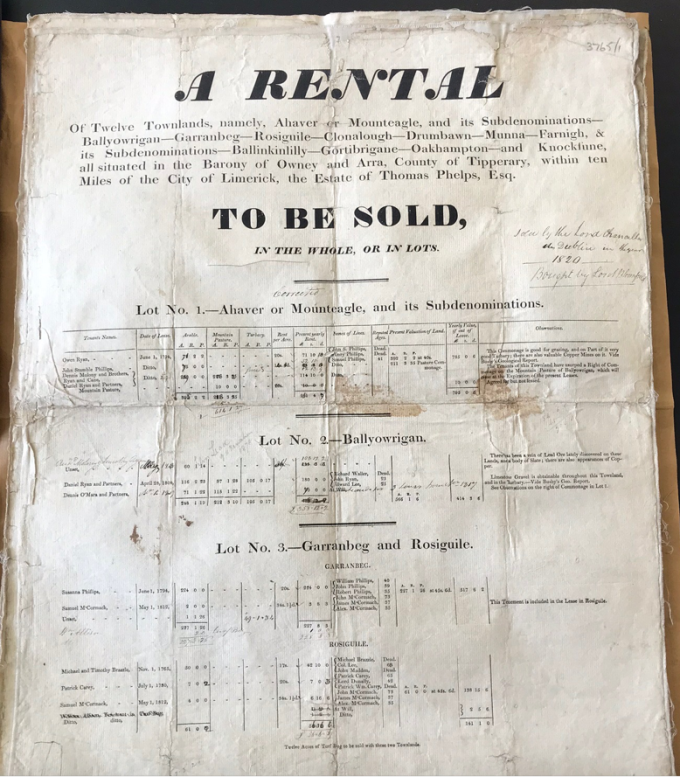

Back in Moyallen, Thomas Phelps became chair of the Armagh Linen Trade and in 1814 advertised in the Belfast Newsletter for a ‘servant to act as groom and own man, must be able to take care of of a gig and attend table.’ In 1815 he moved to Dublin and worked with his brother George as linen merchants at 92 Capel Street. Meanwhile he joined the Tipperary meeting because of the family country seat at Noan. Thomas went bankrupt in 1818 as the notices below show.

In 1820, many Phelps properties all over Ireland were retaken by the Crown under the Encumbered Estates Act because their revenues were inadequate to pay the Crown rents. (4) A letter from Thomas’ son, John Lloyd Phelps, said:

‘Phelps estate sold by the Lord Chancellor at the Four Courts Dublin 1820, the entail having been cut off by my father (Thomas Phelps) to please his father-in-law, Sampson Lloyd, Esq., a banker, before the marriage of my mother, Charlotte Lloyd.’

The entail meant that the inheritance of the estate could not be changed.

The buyer of these 3200 acres in the Barony of Own and Area was Sir Benjamin Bloomfield, a retired major general, private secretary to the king and keeper of his ‘privy purse’. He paid £ 43,000 for the 12 town lands and in 1825 became Lord Bloomfield of Okehampton and Redwood, County Tipperary. The first page of the enormous sales agreement is shown below. (?)

Representatives of the Tipperary meeting tried over a year to arrange a meeting with Thomas. Finally he was disowned early in 1823. One report says he had a daughter that same year named Hannah. Undeterred, Thomas continued in business in Dublin with his brother John until 1829.

Thomas moved to Graignon in the Barony of Middelthird in Tipperary and set up a mill there. However, when the Thurles court determined that he had no right to the mill because it was built on public land, he was forced to sell all the furniture, equipment and stock from his Graignon farm.

Thomas never remarried and spent his last years as a farmer at Noan House, at Thurles, Tipperary. He died there 13 March 1841.

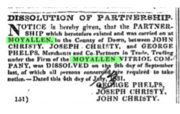

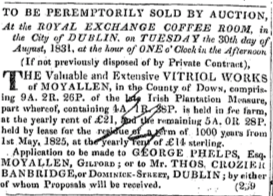

Joseph Phelps died unmarried 9 January 1851 and was buried at Moyallen. Since 1761 the Christy brothers had been selling oil of vitriol, in today’s words sulphuric acid. Then in 1786 John Christy partnered with Thomas Phelps and others to form Moyallen Vitriol Company for its production. This new means of bleaching the linen cloths quickly replaced the traditional ’grassing’ and for a time was quite successful. (17) Joseph and other brothers succeeded his father as partners in the vitriol firm and he was recognized as one of the ‘extensive bleachers and linen merchants’ in Moyallen.

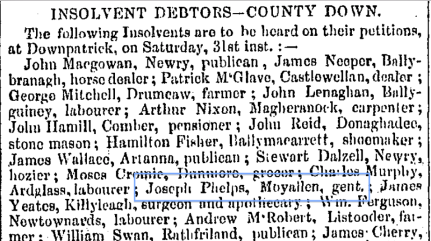

About 1824 Joseph moved to Dublin to pursue the linen trade with his older brothers and supported his brother, Thomas, in the new school he promised in Graignon. However his later life was not a financial success: he was one of the insolvent debtors who were before the court in Downpatrick, County Down, 31 October 1840. (22)

Joshua Phelps, born 3 December 1775 – more below.

John Phelps, born 12 June 1777, died unmarried and was buried at Moyallen 2 December 1838. The Lurgan meeting sent representatives to discus a complaint against him in 1815 but the result is unknown.

Sarah Phelps, born 26 August 1778, died unmarried 20 March 1857 and was buried at Moyallen.

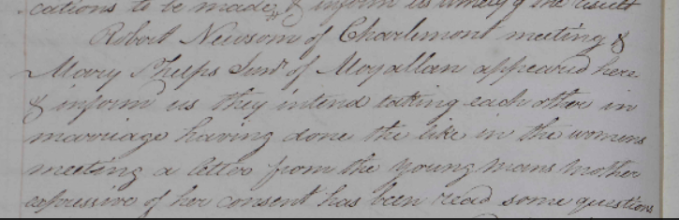

Mary Phelps, born 13 January 1780, on 23 January 1800, married Robert Alexander Newsom (1777-1844) and died 20 December 1843 at Mount Wilson, Edenderry, County Offaly, mid-way between Dublin and Limerick. Mount Wilson took its name from a famous Quaker missionary and Edenderry became a centre for formerly English Quakers.

The Newsom family had long owned the 204 acre Mount Wilson estate and its famous and ancient avenue of yew trees. In the early 1700’s Quakers had built a woollen cloth plant there which employed about 1100 and Robert Newsom might have been a partner. The Newsom family was certainly well known among the leading Irish Quakers.

The Newsoms had six children: Lydia (1805-1869), Maria (1803-1872), George (1806-1864), Joseph Phelps Newsom (1807-1876), Elizabeth (1815-1886), and Robert Wilson Newsom (1821-1867), a Dublin law clerk. Joseph, the second son, soon became a successful and respected iron and coal merchant in Limerick as the newspaper advertisements, extraordinary at that time, illustrate.

Years after his death the Limerick Chronicle published a glowing recollection of Joseph’s business and ethics:

‘Joseph Phelps Newsom, a Quaker, started his business selling Smith’s coal and bar-iron in a yard in what is now known as Upper Denmark Street, but which was known during Newsom’s tenure as “Newsom’s Lane”. Like all other members of his faith, Newsom was strictly honest and upright. He is recorded as having continually assisted the poor impoverished nail workers by making the iron they required and accepting some of the nails (clouts) as payment… Newsom’s business prospered and in due course his premises were extended to William Street. The integrity of the firm is, and has been, a bye-word down through the years. Though the original proprietor has passed on, his name is much in evidence over the grand new premises in William Street and the yard where he sat beside his heaps of coal and iron is now a parking lot for the firm’s customers’.

William Phelps was born 20 May 1781 and never married. First at Portadown then in Waterford, he worked as a merchant. Then in Belfast from 1807 to 1816 he imported and sold an endless variety of goods from tea to horse hides to potash, advertising his wares regularly in local newspapers.

William advertised for ‘a working kitchen gardener’ in 1808 and ‘A Smart Lad, whose Friends reside in Town, will be take as an apprentice. No fee required’ in 1810 but in 1812 his advertisement was to rent out ‘a capital store in Corn Market’ and ‘2 houses to be let in St. Patrick St.’ He went bankrupt in 1815 and soon left Belfast. Bankruptcy proceedings carried on until 1820.

William was accordingly disowned by the Lisburn meeting in 1815 as the following minute shows.

‘Whereas William Phelps son of the late Joseph Phelps of Moyallon who had his birthright among us the people called Quakers; by not attending to the limitation of truth in his pursuit after Wealth, did engage in an extensive line of business, also in speculations without sufficient ?? without considering how much he was Risking the property of others and after he notwithstanding increased his losses by continuing to make new engagements which reduced his prosperity so much that little is left to pay his Creditors we therefore disapproving of such proceedings cannot continue to hold religious Fellowship with him & to hereby disown the said William Phelps from membership with us the said people.’

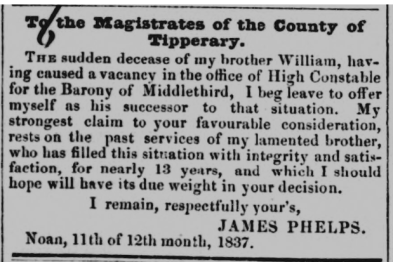

William moved to Dublin and later leased a 77-acre property and house on the Noan estate in County Tipperary. In 1824 he became High Constable, or chief tax collector, for the Barony of Middlethird at a salary of £ 300 per year, a role in which Quakers were favoured because of their honesty and truthfulness. The Dublin meeting in 1834 agreed to ‘accept his resignation & do not consider him any longer a member of our Society’. William ‘died suddenly in a cabin at Noan’ in December 1837 and was buried at Billliebrado. The remaining lease of the property was soon sold.

James Joseph Phelps was born 17 August 1782 in Moyallen. By 1813, he was in the grocery business in Limerick with his brother Samuel. On 29 June 1814, James married a fellow Quaker from a very prominent pioneer Scottish family, Anne Lecky of Kilconnor, County Carlow. The Irish Examiner reported on 11 June 1817, ‘Stores of J & J Phelps attacked by a mob in Limerick and considerable quantities of oatmeal, flour, and some corn taken away’. He was disowned by the Dublin meeting in 1820 for the bankruptcy of the trading firm he owned with Jonathan Hill and he was again disowned by the Limerick Quakers in March 1830 because he:

‘has failed in the payment of his debt which appears to have arisen from a want of sufficient attention to the limitations of Truth by extending his business beyond his capital would warrant whereby loss has been carried to his Creditors and reproach brought to our Christian profession.’

Anne died in 1834 and James moved to New South Wales. Back in Ireland by 1837, he immediately endeavoured to succeed his brother, William, as High Constable for the Barony of Middlethird but was unsuccessful.

James had an impressive estate, Prospect Hill, just south of Limerick and adjacent to the Harvey family estate. He lived also with Samuel at Noan, a property owned by his sister, Mary. He died in January 1839 at Roan House near Cashel, County Tipperary. The Limerick Chronicle described him as ‘partner in a highly respected mercantile firm of that name’.

James had an impressive estate, Prospect Hill, just south of Limerick and adjacent to the Harvey family estate. He lived also with Samuel at Noan, a property owned by his sister, Mary. He died in January 1839 at Roan House near Cashel, County Tipperary. The Limerick Chronicle described him as ‘partner in a highly respected mercantile firm of that name’.

The first of James and Mary’s eight children was Elizabeth Lecky Phelps (1819-1908). In 1861 she married the eminent botanist, William Henry Harvey, F.R.S. (1811-1866), the son of very prominent Quaker bankers and neighbours, but had no children. Her sister, Jane Hannah Phelps (1825-1892) married William Harvey’s brother, Joseph Massey Harvey.

James and Mary Phelps’ first and second sons, John Lecky Phelps and Joseph James Phelps, worked for a short time for Joseph Phelps Newsom’s hardware firm in Limerick. Then they headed to Australia and made a fortune. E. H. Bennis described the approach the brothers took in ‘Reminiscences of Old Limerick’ and their great success in the 1850’s:

‘these two young men decided to go up the Murray River for some hundred of miles and pegged out a great ranch which they stocked with as many sheep as they could afford…Then the bane of every Australian farmer occurred, a prolonged drought, and sheep began to die by hundreds. But the two Limerick settlers dammed up the Murray River and bought up all the sheep they could at lower and lower prices. Down the river farmers wondered what had become of the water and got the Government to investigate. The dam was found and the builders ordered to break it down, but they took no notice. Again and again the Government ordered its destruction to no purpose, so finally they sent a gang of navvies who soon let the water out, but a slick would have it, rain came a day or two after and sheep began to advance in price. Then not far off, gold was discovered in a sterile stony district and fat mutton fetched fabulous prices. After disposing of their stock they sold their ranch at a big profit and returned to Ireland to spend their “well earned” fortune in their native city of Limerick.’

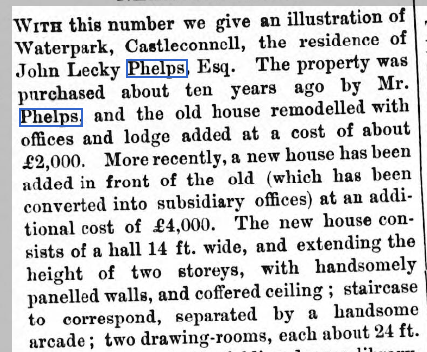

John Lecky Phelps was born in 1815. Returning to Ireland with his fortune, he married Georgina Mansell in 1856 but she died shortly after. In 1862 he spent £10,000 to buy from the Harvey family the old Waterpark estate on the north bank of the Shannon up river from Limerick. Then in 1864 he married Rosetta Anne Vandeleur (1838-1911) from a very prominent and wealthy County Limerick family. He was appointed a Justice of the Peace and bought more property on the Broadford Estate in County Clare in 1878.

Several large great houses were built in the area of Waterpark in the second half of the 19th century and John Lecky Phelps’ home with its magnificent Italian marble staircase was among the most elegant.

John Lecky was involved as landlord and farmer at both Waterpark and Broadford and his family participated in an endless variety of social, charitable, athletic and cultural events. He died in Florence in 1881 while Rosetta Anne died in 1911 in Dublin. Among their ten children, the death of the third daughter, Mary Francis Phelps, was particularly sad. Married on 6 July 1892 to Captain Bernard Hervey Randolph, they both drowned en route to India in the wreck of SS Roumania on 28 October that year. Waterpark stayed in the family until 1914 and was demolished in 1942.

The second son, Joseph James Phelps, born about 1817, left Limerick in 1848 and joined the Quaker meeting in New York before going on to Australia. As described above, his sheep station covered over a million acres and he kept it for many years. The news report of a public hearing in 1869 on the valuation of his Albemarle property described it;

It has a frontage of thirteen miles to the splendid navigable river called the Darling. It is said to be the best run in what we call Riverina; as a proof, the most fat cattle and sheep go from it; and so pleased was the owner with the management of his station, that it is said he some time ago made a present of a thousand pounds to his manager…it is worth calling a garden. The grapes are abundant; the oranges and lemon, the figs and bananas, are also flourishing; while the vegetable kingdom is well represented. The home-stead has in itself an air of comfort and happiness about it which, indeed, may well be envied by our Darling squatters’.

Joseph James was also a member of the New South Wales legislative assembly from 1864 to 1877.

Back in Ireland, he married Mary Allen in Killaloe, County Clare, in March 1875 and was a commissioner to the Philadelphia Exhibition in 1876. He died at Willowbank, the family estate on the south bank of the Shannon in 1890. His wife, Mary, lived until 1894 and was ‘held in the highest esteem in the locality which her presence so long graced, and her charity and consideration for the poor were proverbial.’ Their one son, Thomas Herbert Phelps, was born in 1879 and died unmarried in 1906.

The third son, Robert Lecky Phelps, born 1820, spent 20 years farming in South Africa before going to NSW where he founded Valverde winery near Albury in New South Wales. He married Josepha Petley and died at Middle Brighton, Victoria, in 1916. His son, John James Phelps never married but became the manager of Joseph James Phelps’ sheep station and later a merchant at Corryong, a village on the upper reaches of the Murray River. He died the same year as his father and the Corryong Reporter on 6 July 1916 printed:

‘He was a bachelor, and a man of quiet, retiring disposition, with a bent for very plain living. Though a prey too certain shortcomings, those who secured his intimacy found him a staunch and true friend and a man of various parts. Before coming to the Murray he was manager for his uncle of one of the largest sheep stations on the Darling, and in his day had few rivals for wool classer’.

James and Mary Phelps’ other children were James and Mary who died young and Lydia Matilda who died unmarried in London in 1902..

George Phelps, born 3 October 1783, was another child of Joseph and Mary Phelps. He died unmarried 22 April 1866 and was buried at Moyallen. His sister, Elizabeth, was his executor. George was a director of the vitriol company until its dissolution in 1831 and the sale of its properties. The reports from The Belfast News-Letter follow.

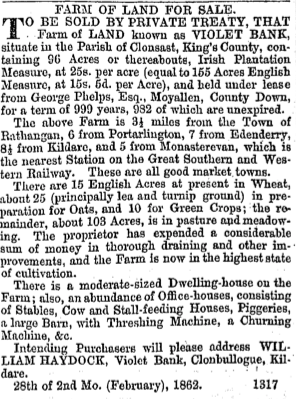

In 1847, George was also among the signers of the Council of the Chamber of Commerce opposing the Dublin Improvement Bill. Another news report shows he had interest in other properties as late as 1862.

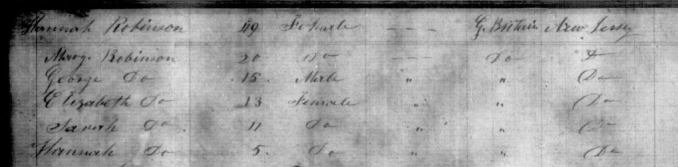

Hannah Phelps, born 11 March 1785, in Moyallen and on 24 August 1809 married George Robinson, a farmer from Moate, a village about 140 km. west of Dublin. George’s debts led to his being disowned by the Moate Quakers in 1816 and the family moved southwest to Newtown in King’s, now Offaly County. George about 1828 left Ireland for New York leaving two sons in Ireland but taking the eldest, Henry, with him. That same year Hannah moved to Dublin for her last child, Hannah Louisa. In 1834 with five of the children, she sailed on the ‘Eagle’ to New York rejoining George in the Quaker meeting in Rahway and Plainfield, New Jersey.

The family moved to New York in 1840 but George died in 1843.

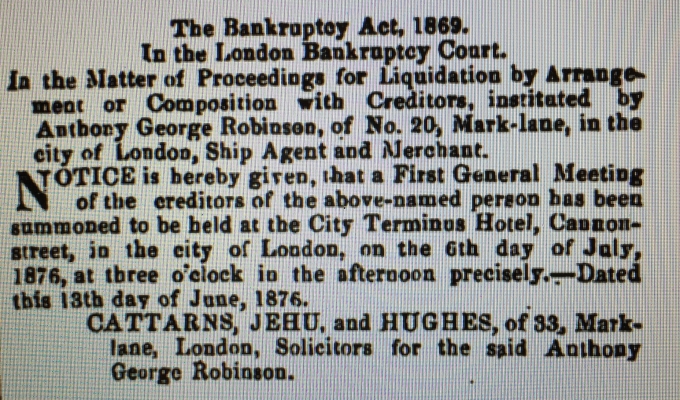

As to the Robinson children, Mary (1810-1897), married Charles Wingate in 1839 and they had three boys and four girls. Daughter Sarah married George Hartshorn. Two daughters, Elizabeth and Hannah Louisa, lived in Woodbridge, New Jersey, with their mother until Hanna Louisa married James L. Lyman in 1848 and moved to Catskill, New York. Her mother, Hanna, died and was buried there in 1869. Elizabeth (1810-1897), had been educated at the Leinster Provincial Friends’ School before emigrating and returned to Ireland. (more below) The eldest son, Henry (1810-1858), operated a coal business in New York in partnership with his brothers. Anthony George Robinson (1815-1897), the second son, developed an important shipping agency and banking interests in London including part ownership of the St. Petersburg Steam Ship Company. One of Mary’s sons, Charles, worked for Anthony’s firm in London for six years. The London Gazette reported Anthony’s bankruptcy 16 June 1869.

George Robinson (1819-1902) owned a ship building yard in Cork and delivered the new 579-ton steamship ‘Avoca‘ to Malcomson and Co. for its Dublin to London line. His brother, Joseph Phelps Robinson had a brief but most unusual career. After forming a close and lasting association with Joseph Robinson Pim in their Liverpool apprenticeship, he arrived in Sydney in June 1842, a partner of the colourful financier/adventurer Benjamin Boyd. He was the resident manager of the Royal Bank of Australia when it went bankrupt but the large Australian properties he had bought and English businesses saved him. He was elected to represent Melbourne in the New South Wales Legislative Council from 1843 until his death at 33 in 1848. His many charitable acts earned him the name of ‘Humanity Robinson‘. Joseph also funded exploration of the islands of Australasia, one of them named ‘The Kingdom of Mosquito’. The 1847 cartoon below makes fun of Benjamin Boyd’s ship ‘Wanderer’ and Joseph’s exploration ventures.

Joseph Phelps Robinson’s bequests included his Australian property plus interests in two banks, two shipping companies, the New York coal yard, a beer business, a railway, as well as cash for each of his parents and siblings. However we have no idea how much these varied items and promises were worth. For example, the St, George Steam Packet Company went broke in ?

Other children of Thomas and Mary Phelps included Elizabeth Phelps, born 19 September 1786. She lived at Moyallen House, died unmarried 4 January 1872 and was buried at Moyallen.

The last child, Samuel, was born 30 May 1788 at Moyallen. At the age of 18 he began an apprenticeship in Limerick but was soon in trouble with the Limerick meeting: he had to be ordered to pay some 20 pounds for the new Belfast meeting house. In 1817 he was granted a license to marry Mary Mcconnell but here is no evidence that they did marry. The next year he was disowned by Limerick Quakers due to:

‘criminal connection with a young woman for which as well as other inconsistencies he has been privately laboured with without having (?) produced the desired (?) affects.’

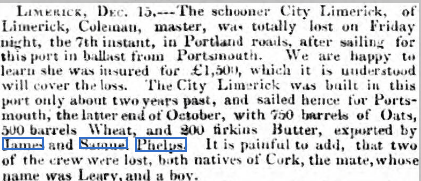

Still in Limerick in 1824, Samuel and James were merchant traders in farm products. In December 1827, The Southern Reporter and Cork Commercial Courier reported the loss of the ship ‘City Limerick’ and its whole cargo of their exports. They again exported a cargo the following year.

Later Samuel returned to Moyallen and farming and in 1839 he was considered there an expert in growing potatoes from cuttings, a totally new approach. Finally in 1845 he was advertised as the agent for Belfast and its vicinity for a farm insurance firm. He died in Moyallen 25 July 1847 and was buried there.

Note that only five of Joseph and Mary’s children married. Quakers lived in a closed circle where marrying a non-Quaker brought immediate disownment, a constraint which was not softened until 1864. Note too that the three sons who did marry joined prominent Quaker families but financial success had to await another generation. Several sons, usually working together, carried on as merchant traders in linen and other products. This role had enriched their grandfather and father but times had changed: there was no longer any profitable place for such middlemen. Britain’s Free Trade Act of 1846 put an end to farm-based linen production in both northern and southern Ireland but widened the opportunity for its manufacture in the large factories in Ulster.

Ireland endured years of social and economic troubles after the Napoleonic wars ended in 1815. As described by Canadian writers, Hoffman and Taylor: (26)

‘Absentee landlords and their drive for financial gain compounded an already desperate situation caused by famine, fever and crop failures between 1817 and 1821. Political reconstruction under the Act of Union of 1801, industrial competition, a tremendous population growth, sectarian animosity and dispossession all took their toll. Long practiced in exporting her labourers as a means of coping with poverty and unemployment, Ireland was now poised for the commencement of what would become one of the largest migrations ever.’

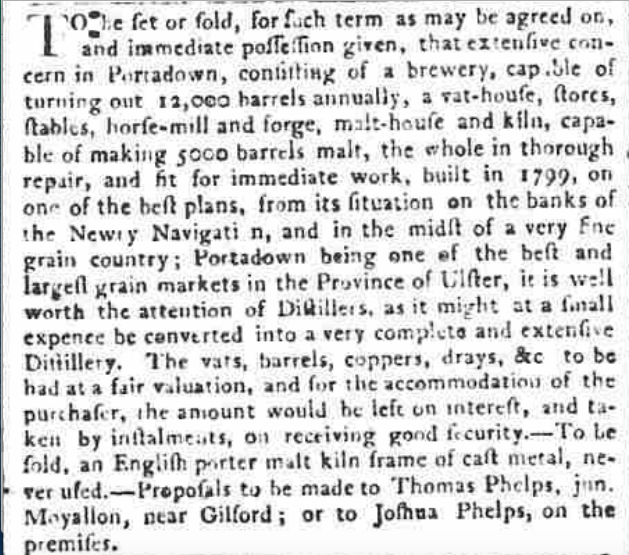

Born in 1775, Joshua Phelps was one of my great-great-grandfathers. In partnership with his brothers, James and Thomas, Joshua founded a brewery on the Newry River at Portadown in 1799 and was its onsite manager. He advertised in the Belfast News-Letter for the various staff needed: in 1799 for a cooper, in 1802 for a clerk ‘who can write a good hand, understand accounts and who does not object to the business of a brewery’ and for 2 draymen, a stable boy and a smith in 1804 for the Joshua Phelps and Co. Brewery. He also offered for sale many items such as imported timber in 1803, probably from brother William’s Belfast stock.

As to Joshua’s marriage, the Lurgan meeting minute book recorded 15 January 1803: (19)

‘Josa Phelps & Eliza Greer both of this meeting appeared here and declared their intentions of taking each other in marriage having done so in the Women’s meeting now sitting. Thomas Malcomson & William Bell are appointed to join women friends in making the necessary enquiries respecting their clearness from other marriage engagements & cause their intentions to be duly published & return account to next monthly meeting.’

Joshua married Elizabeth Greer 13 March 1803, the year after many of their closest relatives had been disowned by the same Lurgan meeting. Their marriage declaration was similar to that of his parents and witnessed by many Phelps, Christy and Greer relations. Eliza was born 16 April 1781 and was the daughter of James and Jane Greer of Clanrode. This Quaker family was had wealthy connections and had been prominent in the Lurgan area since the 1600’s as reported by Vann and Eversley: (18)

‘In the seventeenth century (the Greers) were clearly still agriculturalists, mostly in the Lisburn and Dungannon area. However, by 1700 some were clearly engaged in spinning and weaving: mostly flax, but also wool. Looms begin to figure in their inventories and distraint for tithes was made in quantities of yarn. By 1710, we find them as linen drapers at Lurgan which means they acted as middlemen between producers and Belfast merchants. By the time of Henry Greer of Lurgan (born in 1716) they were clearly rich; he possessed extensive tracts of land, some of which he had bought from the great families of the area. In 1766, Henry for his second wife married of the Pims of Kings County, one of the wealthiest of the Southern Quaker families.’

The year after his marriage, Joshua and his brothers, Thomas and Joseph, leased 25 acres in the Townland of Ballyoran, Parish of Drumcree, a part of Portadown. (22) However, with a growing family, problems were beginning to show.

Probably because of competition and their inexperience, Joshua and his brother, Thomas, recognized in 1806 that the brewery was not a financial success and endeavoured to sell all the equipment, some of it never used.

There is no evidence that Joshua was involved in the brewery after 1806. It was still for sale in 1819 and anyone interested was asked to contact John Phelps Jr. in Dublin. Joshua was never a partner in the vitriol company and a letter in 1808 recommended him for a modest post as a linen inspector in Tandragee. (4) In 1813, he rented his house and store in Portadown and turned to farming. They moved again to Tandragee and the Richhill meeting and the Lurgan minute book recorded their move: (19)

‘18 March 1815. Joshua Phelps and his family having removed to reside in the bounds of the Richhill meeting, Joseph Gough and William Crothers are appointed to prepare a Certificate of Removal & bring it to next monthly meeting for approval.’

The Richhill meeting had problems as well. A well-known English Quaker in 1813 described the state of Quakers there: (25)

‘Many of the Friends are in low circumstances; some of them living in poor cabins, and apparently strangers to much of what we consider the comforts of civilized life, but generally in a state of independence, holding a small portion of land, from six or eight to thirty or thirty-five acres. They grow their own flax, which is spun, and in many instances woven in the house, and sold in the market as it is made. This is the support of most of the inhabitants in this populous province. Almost every family has a little land …So there is scarcely a family without a cow and whose land does not furnish their own peat.’

Returning to Lurgan and its Quaker meeting in 1819, Joshua and family found little comfort. John Conran, the sole remaining minister in 1822 described that sorry time: (20)

‘The Monthly meeting held in Lurgan (was) a very small gathering and a poor low time…Under painful exercise I felt on account of the meeting (about eight or nine men), I told them I remembered when there were 63 families who were esteemed in membership and about 60 families not in membership when I visited them.’

On 15 February 1823, the Lurgan meeting learned that Joshua and Eliza after 20 years of marriage planned to leave for Upper Canada with most of their children. Even more surprising, Eliza was pregnant and they had no idea as to where they would settle. The Certificate of Removal was approved 19 April 1823 and read as follows: (19)

‘To the Friends of the monthly meeting of Yonge Street, Upper Canada, North America. Dear Friends: Joshua Phelps and Eliza his wife with their children, Henrietta, Thomas, James, Alfred, Caroline and Joseph have removed from hence with the prospect of getting in the bounds of your monthly meeting – We have to inform you that they are members of our religious society, that Joseph and his three eldest sons were in the practice of attending our meetings for worship and discipline fairly regularly – and that Eliza & her eldest daughter attended them at times. On enquiry, they have left us in solvent circumstances. We recommend them to your Christian care and oversight & are your affectionate friends.’

The Certificate was signed by 19 members of the meeting but no Phelps or Greer names appear and only two Christy names. The strong family support apparent at their wedding was totally missing. My thesis is that Joshua and Eliza stayed closer to the traditional conservative Quaker practices than their many of their relatives and were increasingly estranged from them. Joshua did not have the financial success of his father and father-in-law or the entrepreneurial spirit of his brothers. But they were not poor: we have inherited silver spoons, several porcelain Spode cups and a mahogany writing desk which they brought with them to Upper Canada.

From their studies, Vann and Eversley described the general characteristics of Irish Quaker emigrants in this period: (18)

‘Whatever Friends were, they were not impoverished peasants. We have found none who were subject to eviction or rack-renting or the other evils of Irish landlordism so familiar in Irish history. When Friends emigrated to America, as many did, it was sometimes as a result of decay of trade, but they did not emigrate as paupers, and their motive was to find a better living, not to escape persecution or intolerable hardships in Ireland.’

Three of Joseph and Mary Phelps’ children stayed in Northern Ireland.

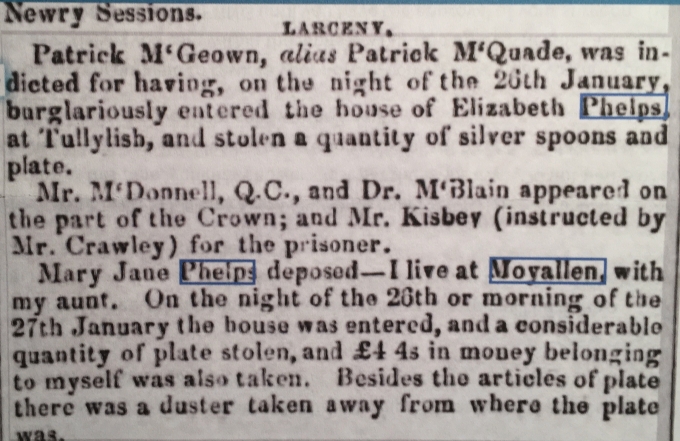

Mary Jane Phelps, born in 1808 lived unmarried at Moyallen House with her aunt Elizabeth until her death 30 November 1873. She owned a nine-acre property in Gilford and her uncle, George Phelps, bequeathed her his six-acre farm at Ballymacanolan. In turn, she left £ 20 to sisters, Anna Sophia Phelps Pim, and Sarah Phelps in Upper Canada plus £ 20 pounds to her brother, Joseph Greer Phelps in Australia and her niece, Edith Emily Phelps Pim. The Downpatrick Recorder published on 11 March 1871 her testimony in the trial of the man accused of stealing from her home.

Anna Sophia Phelps, born 18 November 1813 in Portadown, on 16 March 1836 married George Clibborn Pim (1807-1882), a wealthy partner in the agency for the Waterford Steam Ship Co.’s service between Belfast and Liverpool. They lived in Moyallen Manor (or Ville) until she died 8 March 1875. When her husband died in 1882, the Belfast Newsletter on 2 February reported:

‘Death of George C. Pim, Moyallon – Senior partner of the firm of Messrs. George C. Pim and Co. died at his residence, Moyallon. Mr. Pim had suffered from ill-health for a long time, so that the occurrence was not unexpected. Paralysis was the cause of death. His life was remarkably successful, success being the result of his great business talent and the reward of diligence. He was a most amiable gentleman and his friendships were old and firm. In his benefactions he was liberal and judicious. Many poor persons in his own locality were almost entirely supported by him and he was a generous employer. His sympathies were wide and class and creed were no obstacles to the exercise of his generosity’.

Anna Sophia and George Pim had five daughters and five sons: Mary (1837-1865), Alfred Joshua (1838-1856), Hanna Elizabeth born 1840, Sophia born 1842, George Frederick born 1844, Thomas Wakefield Pim (1845-1920), Joseph Phelps Pim born 1847, John William, born 1849, Edith Emily born 1852 and Alice Gertrude Phelps Pim born 1855. Edith Emily never married and sadly died in the fire that consumed the great house in April 1925. (20)

Frederick William Phelps, born 17 June 1817 in Clanrold, Shankill Parish, County Armagh, died there 2 December 1818 and was buried in Lurgan. Edmund Phelps was born and died in 1819.

As a follow-up to the Revolution of 1798, the British Parliament’s Act of Union in 1801 was envisioned as a new start for Ireland but it did little to solve the ‘Irish problem’. It merged the governance of Ireland and Britain and abolished the Irish legislature, but the following years brought deeper divisions between the Protestant north and the Catholic south.The potato famine and mass emigration of the 1840’s did nothing but stoke the north/south divisions. Laws restricting Catholic rights were repealed by The Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829, but revolts were unending. After decades of turmoil in Parliament, the British finally passed The Home Rule Act in 1914 but it was suspended until the end of World War I. It was 1922 when the Republic of Ireland finally became independent and the six northern counties opted to remain part of the United Kingdom. Still ‘the Troubles’ continued. (2)

SOURCES

1. ‘Irish Linen – the Fabric of Ireland’, D. M. McCrea, Living Linen Project, 1971.

2. ‘Industrial Dublin Since 1698 & the Silk Industry in Dublin0’, J. J. Webb, Maunsel & Co., London, 1913.

3. ‘Friends in Life and Death’, D. T.. Vann & D. Eversley, Cambridge University Press, 2002.

4. Wikipedia.

5. ‘The Irish Quakers’, M. J. Wigham, Historical Committeof the Society of Friends in Ireland, 203.

6. ‘Lurgan Ancestry Project’, Lurgan, Northern Ireland.

7. Sinton Family Trees.

8. ‘A Biographical Dictionary of Irish Quakers’, R. S. Harrison, Four Courts Press, 1997.

9. ‘Six Generations of Friends in Ireland (1655-1890)’, J. M. Richardson, London, 1894.

10. Lurgan Quaker meeting minutes.

11. Burke’s Irish Family Records, 1976.

12. Dublin Quaker meeting minutes.

13. .

14. Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), Dublin, Ireland.

15. .

16. ‘A Narrative of Events that Have Lately Taken Place in Ireland: Among the Society Called Quakers’, W. Rathbone, Belfast, 1804.

17.